For more than two decades, Kathleen Conlee, our vice president of Animal Research Issues in the U.S., has been working to end the use of animals in testing and research. But before she became an advocate for animal protection, she worked at a breeding facility that supplied primates to laboratories for research and testing. In this guest blog, I’ve invited her to tell us more about how this shaped her perspective and what life is like for animals inside these places.

It all started when I was in class as an undergrad and heard people talking about feeding fig bars to monkeys. Before I knew it, I was studying rhesus monkeys in a lab on campus, and I was so fascinated by them. I wanted to spend my days learning about and working with primates.

But when I visited a facility that had monkeys living in small, barren cages, and I saw how they trained the animals to sit in a restraint chair for procedures to serve some scientific inquiry, I couldn’t picture myself doing that directly. At the time, though, I still wanted to work with primates and believed primate research was important for human health; seeking another avenue, I ultimately landed at a monkey breeding facility in South Carolina within weeks of graduating college.

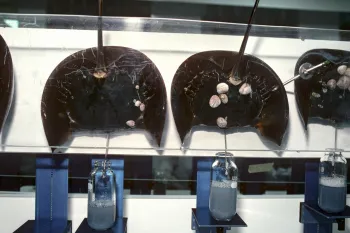

The company I worked for had thousands of monkeys, mostly macaques, that they would breed and sell to research laboratories. I thought animal testing and research was necessary, but I also felt that the animals needed someone to look out for them. Over several years, I saw how millions of dollars in government grants were funneled in to support a system that inflicted terrible suffering on animals. I stopped believing that this was the best we could be doing for human health. Still, I stayed because I became fearful of what would happen to the monkeys if I left.

Kathleen Conlee/Humane World for Animals

The goal at this facility was to make sure the animals produced as many babies as possible. I remember being proud that I reduced the infant death rate and could identify thousands of individual monkeys and their family members. I didn’t think about the fact that while I was preventing their death as infants, I was ultimately sending those animals to a life of prolonged suffering. I was handed lists of numbers and told to pick which animals would be sent out next, filling orders as if they were a product.

We would sometimes receive monkeys from laboratories, and some of them suffered from severe psychological trauma. One, a rhesus macaque named Able, was terrified of anything but his “chow” biscuits and would mutilate himself—tearing his skin—when given anything new, even something as delicious as an apple or banana.

Laboratories with breeding colonies will often share images of monkeys in large social groups in big enclosures. These images are good optics for those who understand that primates are extremely social and need room to play. But there is a lot that is deliberately hidden. Some animals are stuck in small cages for quarantine or particular research protocols—a terrible cruelty for social creatures—or ripped from their families. The company would do “processing” during which the members of each group would be tattooed on their faces and chests, given physical exams and either returned to their group or pulled out for a shipment to another lab. The youngsters, who the day before were bonding with their family, would be put in a small cage and prepped for shipping. Mothers would wake up looking for them, crying out. You could hear the youngsters from a building across the property returning their calls. I can still hear their mournful cries—those will haunt me forever.

While I worked at the facility, I tried to improve the conditions for the monkeys in my care, such as incorporating an environmental enrichment program, adding fresh fruits and vegetables to their diet (they were only receiving “chow” biscuits each day), requiring a physical and behavioral assessment of each of the thousands of individuals every day and ensuring prompt medical or behavioral treatment when needed, and eliminating the use of facial tattoos. The company was ultimately caught illegally importing monkeys captured from the wild—I will never forget how terrified those animals seemed in confinement. I finally decided I just couldn’t do it anymore.

I then went to work for a great ape sanctuary, which was an amazing experience. But I still felt I had to do more for those animals who had not yet been rescued, for those countless others I left behind in the system. Thankfully, Humane World for Animals, when it was still called the Humane Society of the United States, took a chance on me. I remember in my first year at the organization, I read a paper about a painful dental experiment; I realized the macaques came from the lab where I had worked and from the very time when I worked there. I had helped raise them—for that. That was just one group of many—what did the other animals endure because of what I had done? It was painful to consider this, but I felt immensely relieved that I was at last in the right place, doing something to fix it.

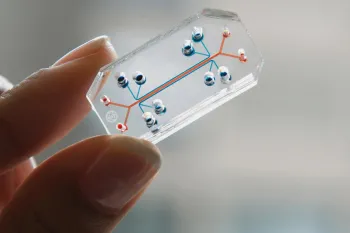

I have been working for more than 20 years to move society away from using animals in harmful research and testing and toward the use of non-animal methods that are more effective and relevant to humans. To this day, I still care about human health AND animals. The good news is that choosing one doesn’t mean hurting the other and, in fact, investing in non-animal methods will ultimately benefit both. Non-animal methods that use human cells or are based on human data can more accurately and effectively predict how the human body will respond to drugs, chemicals and treatments.

I’m proud of the work my team at Humane World for Animals has accomplished: ending chimpanzee research in the United States, securing a commitment by the Environmental Protection Agency to end mammalian testing, passing state laws that prohibit the sale of animal-tested cosmetics, getting 32 dogs who were being used in a pesticide test released from a lab into loving homes, and so much more.

I still have nightmares about the facility where I worked. In them, I am trying desperately to go back there to help the animals, to make sure they are safe, but every nightmare involves some impossible obstacle. I am relieved when I wake up that I don’t work there anymore but I also face the reality of how much more there is to do in real life. It can feel like an endless sprint. When we have a victory and I think, “okay, maybe I’ve done enough to pay my dues,” the thought doesn’t last. And I don’t think it should. The victories won’t be enough until the day when no more animals suffer in labs. It will take all of us to make that happen.

Kathleen Conlee is vice president of Animal Research Issues at Humane World for Animals in the U.S.