Just a few years ago, the world’s largest rodent lived in relative online obscurity. Then, in 2022, capybara memes took over TikTok and a catchy song soon followed. The animals quickly became an internet sensation. Toy companies started making capybara stuffed animals, with one selling out in just two days. Dazed magazine deemed 2022 “the year of the capybara.” To date, there have been over 750,000 TikTok videos posted under the hashtag “capybara” alone.

In a time when wild animals face intensifying threats and dwindling populations, a surge of public interest can be a great thing. But online attention rarely focuses on their wild lives. Instead, we fixate on our own desires to interact with them directly. Cruel wildlife attractions and the wildlife pet trade respond to that demand—all while the animals at the center of our adoration suffer.

When cute content creates real-world harm

Wild animal species have surged and waned in popularity long before the internet. Ferrets became common pets in the U.S. in the mid-1900s. In 1995, The New York Times dubbed the iguana the pet of the ‘90s.

The internet has simply propelled the speed at which animals become pop culture sensations.

Hemanth/Humane World for Animals

One of the early internet darlings, the slow loris, had little online traction before April 2009. That month, a YouTube user uploaded a video of a slow loris sitting on a bed. The animal has her arms in the air as a person “tickles” her. Google searches of slow lorises spiked that spring and stayed elevated before reaching their peak after a YouTube video was posted in March 2011 of a captive slow loris holding a tiny umbrella.

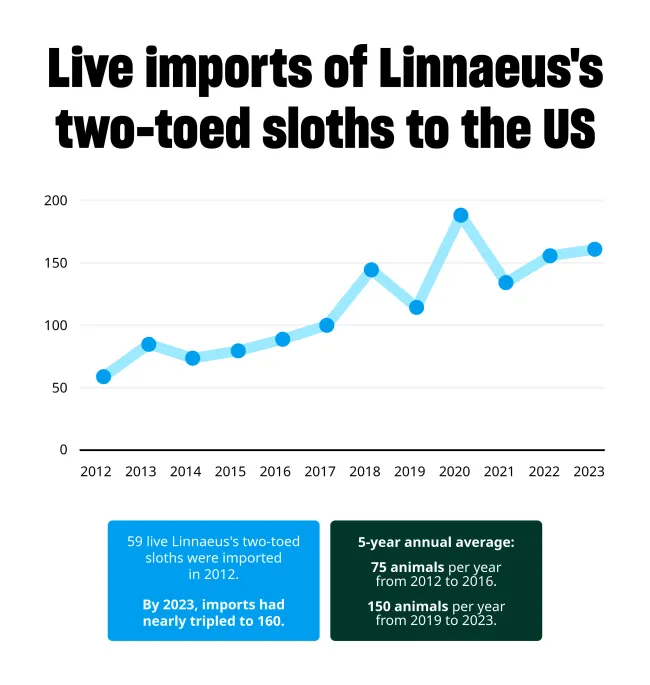

It's a similar trend for other animals. Online interest in sloths has stayed fairly consistent between 2004 and now, minus a spike in April 2013—the same month a YouTuber posted a video that’s since been viewed almost 3 million times of a captive sloth interacting with a cat. Google Trends data shows interest in the term “pet otter” started to rise around 10 years ago, which corresponds with a rise in YouTube videos featuring captive otters in close contact with people.

/The HSUS

Help stop exploitation

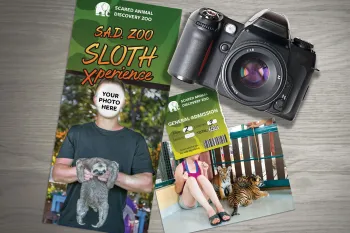

Wild animals should never be props for entertainment. Behind many tourist attractions offering selfies, feeding or hands-on encounters lies a hidden world of suffering. By skipping these experiences, you are taking a stand against cruelty and helping to protect animals.

It’s difficult to analyze exactly how online fame correlates with wildlife exploitation. Data on the legal wildlife trade is limited, and it’s hard to estimate how many animals are being poached for illegal trade. Still, existing evidence and anecdotal reports suggest an animal’s popularity online often moves off screen, where they’re exploited in the wildlife pet trade and at exploitative wildlife attractions.

Laura Hagen, managing director of wildlife protection at Humane World for Animals, has seen an “explosion” in facilities offering direct interactions with capybaras, sloths, otters, and small primates. And Grettel Delgadillo, our Latin American director of programs and policy, has seen a rise in sloth attractions. In the U.S. alone, Humane World for Animals has documented over 135 facilities offering close encounters with sloths, though we estimate that there are many more.

Graph adapted from CITES Sloth Factsheet, 2025/CITES

How the internet can harm animals

To become photo props or kept as pets, countless wild animals need to be bred in captivity or taken directly from the wild.

But many internet darlings are threatened with extinction. All species of slow lorises are suffering population declines in the wild, with two species being critically endangered and four being endangered. The pet trade is a primary driver. The pet trade is a growing danger to threatened Asian small-clawed otters as well.

Individual animals also undergo intense distress to make it into consumers’ hands. Many die along the way.

Poachers often kill protective mother animals in the wild so they can get to her babies. Taken away from their mothers and highly distressed, many of them die in transit (the estimate is as high as 90% for sloths). Animals can also die from painful procedures meant to make them safer for people to handle. Because slow lorises can inflict a venomous bite as a defense against threats, poachers will clip or rip out their teeth. Otters and sloths too can have their teeth clipped or removed entirely.

Animals who make it to their final destination—whether that’s a private home, a wildlife park or a wild animal café—will spend the rest of their lives being exploited for human entertainment.

The HSUS/The HSUS

Our years of investigations reveal a bleak picture. At an Oklahoma attraction, we documented a 6-month-old otter being forced to interact with a line of visitors. He repeatedly screamed and tried to wiggle out of the arms of a worker—who attempted to quiet him by covering his face with her hand. In New York, an undercover investigator visited a sloth attraction where multiple sloths were confined together in a small room despite largely living alone in the wild. Two sloths started fighting while hanging from a tree branch and a worker hit them with a spray bottle more than 20 times, causing one of the sloths to fall to the floor. The facility also had two capybaras who were kept in a tiny, barren cage.

This is just a small snapshot of a reality wild animals endure over and over. When our investigator visited the sloth attraction, the facility offered ticketed interactions for up to 20 people at a time, 11 times a day, six days per week—meaning that, if fully booked, up to 1,320 people could have entered its doors every week.

Looking through a rose-colored filter

Although the animals are often suffering right in front of us, we don’t always know how to recognize it.

Slow lorises have large, doe eyes that make them look cuddly and docile. But they’re actually the world’s only venomous primates, who raise their arms to access the venom stored in glands in their upper arms—not because they like being tickled. Capybaras’ boxy, potato-shaped bodies have probably contributed to their online perception of being “chill.” Sloths’ facial features make it seem like they are always smiling. Plus, they tend to freeze when they feel scared, and they can appear to be hugging us when they’re simply mimicking how they would hold onto trees in the wild.

Kent Gilbert

Because we can misconstrue their distress for friendliness, we may be more drawn to videos where wild animals are suffering. A YouTube video with 29 million views (one of the most viewed videos when searching for “sloth” on the platform) shows a sloth laying with a person on a hammock. The sloth opens his mouth and vocalizes. A voiceover tells viewers the sloth is yawning because he is so comfortable snuggling with the person. But sloth experts say that the “yawn” is actually a sign of stress.

Researchers who studied 100 popular online videos of slow lorises found a similar phenomenon. Only two of these videos showed slow lorises in a natural setting. These videos got significantly fewer views than ones where the animal seemed distressed or were exposed to unnatural conditions.

A turning point for captive wildlife

For animal welfare advocates and conservationists, it’s incredibly difficult to push past the cutesy veneer of viral animal content and educate the public about what is really happening. There have been positive steps, though.

Humane World advocates for stronger protections for species targeted by the wildlife trade. Much of this work revolves around CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), a treaty that regulates the international wildlife trade. In 2019, with our support, two Asian otter species received the highest levels of protection, effectively banning their international commercial trade. And last year we supported a proposal that will regulate the international trade in Hoffmann’s two-toed sloths and Linné’s two-toed sloths (also known as Linnaeus’s two-toed sloths) for the first time ever.

We’re also working to reduce demand for captive wild animals. In Costa Rica, we’ve partnered with the country’s government on a campaign called #StopAnimalSelfies to educate tourists about the harms of direct interactions with wild animals.

The internet itself can also help create positive change. When a video of a slow loris being tickled was first published in 2009, people largely commented about wanting their own slow loris, researchers found. But over the years, the tone of comments shifted as campaigns raised awareness about how the pet trade hurts slow lorises. The number of comments about wanting a slow loris declined, and comments expressing concerns about animal welfare and conservation became more common.

Still, increased awareness about the plight of one specific animal hasn’t translated into broader concern about all wild animals exploited for human entertainment. In many online videos featuring captive primates, otters, sloths and capybaras, the comment sections are overwhelming positive, with most people making jokes, gushing over the cuteness of the video or expressing their desire to interact with the animal directly.

Meredith Lee/Humane World for Animals

At Rescate Wildlife Rescue Center in Costa Rica, online hype is helping spotlight the organization’s work rescuing and rehabilitating wild animals in need. After Costa Rican authorities seized five capybaras from the illegal wildlife trade last year, the organization took the animals in. The animals were in poor shape and one died shortly after being rescued. Because capybaras aren’t native to the country, the four survivors will spend their lives at the accredited sanctuary.

Ever since the capybaras arrived, attendance has surged as people clamor to see the internet celebrities in real life. Here, visitors watch the capybaras from a respectful distance. Their admission fees help fund wildlife rehabilitation efforts and ongoing care for animals who cannot return to the wild. Visitors can’t pet or hold the capybaras for a selfie. Rather, they get the rare opportunity to observe the animals behaving as they would in the wild.

On a November day, a crowd forms around the capybara enclosure. The animals playfully chase each other and splash in their pool, completely unaware of their newfound stardom.

Related stories

Christi Gilbreth/Humane World for Animals

Freed from the pet trade, George the marmoset finds sanctuary at Black Beauty Ranch.

Photo collage by Rachel Stern/The HSUS

Many people are drawn to animal attractions out of a love for animals but end up inadvertently supporting cruelty. Here's how to avoid exploitative wildlife attractions.

Audrey Delsink/Humane World for Animals

Learn how souvenirs, exotic pets and wildlife products fuel the global wildlife trade. Discover cruelty-free travel tips to protect endangered species and avoid supporting animal exploitation.