On Oct. 1, Jane Goodall DBE, founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and UN Messenger of Peace, passed away. Goodall’s name became synonymous with conservation and animal protection due to her contributions to improving the lives of animals, including wild chimpanzees and primates used in laboratory experiments for medical research. Goodall worked directly with us on our successful petition to change U.S. Endangered Species Act regulations that deprived captive chimps of protection, which allowed them to be used in invasive experiments, circuses, roadside zoos and the pet trade. She testified to the U.S. Congress in support of the CHIMP (Chimpanzee Health Improvement, Maintenance and Protection) Act, which created a federal sanctuary system for chimpanzees no longer used in research, giving these chimps the chance to live out their lives in an environment as close to nature as possible. And we worked with her team when she signed off on an expert declaration about the negative impacts that U.S. research and the pet trade had not only on the welfare of individual chimps, but on the conservation of the species.

She made history by inspiring generations of people to love animals and to care deeply about their welfare. Goodall’s influence on the animal protection community is immeasurable, and her work on behalf of primates and all animals will never be forgotten. Here, Jeff Flocken, chief international officer at Humane World for Animals and a friend of Goodall’s, remembers her.

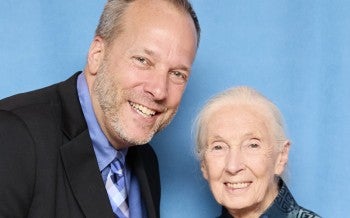

The world has lost a hero for animals this week with the passing of Dr. Jane Goodall. Like many others in the animal welfare and wildlife conservation field, I was inspired by Jane for my whole career in animal welfare. She was also someone who I was lucky enough to collaborate with and consider a friend.

Jane helped the world to see animals differently. Perhaps best known for her trailblazing work studying primates in Africa, back in the 1960s and 1970s, she brought the rich and complex social dynamics and fascinating behaviors of wild chimpanzees—which until then were little known—to wide audiences through the stories and films of National Geographic Society. As a keen and insightful scientist, she was able to observe and document interactions amongst individual chimpanzees, families and troops, and share these learnings with a brilliant storytelling knack that enthralled the world. The scientific community owes a great debt to Jane for breaking the glass ceiling and also for making the field of zoology fascinating, which in turn inspired generations of future primatologists, marine biologists, ornithologists, entomologists and all the other animal scientists who entered the field because of her, and have elevated our understanding of, and respect for, the natural world.

She worked with us at Humane World for Animals (back when we were called the Humane Society of the United States and Humane Society International) to champion getting chimps and other animals out of laboratories, but also to stop the illegal wildlife trade in species such as rhinos, elephants and pangolins; to stop the killing of badgers in the UK; to protect grizzly bears and wolves in the U.S. from cruel trophy hunting and trapping; to ban the trade in animal fur for fashion; and to end commercial whaling.

In 2016, Jane and the Jane Goodall Institute worked with us and a coalition of animal groups to plan for the care of dozens of chimpanzees in Liberia who had been used in medical experiments for decades; this joint vision resulted in our Second Chance Chimpanzee Refuge, where we still care for these chimps, providing them with a safe place to live out the rest of their lives.

It was the initial scientific-study chapter of her professional life that first inspired me personally to commit to a life helping animals. Then I had the honor of working with Jane in the second phase of her career, when she gave up her field work in Tanzania and stepped onto the global stage to become the world’s foremost advocate on behalf of animals and the planet. In this transition, Jane was fearless. She left behind decades of working alone in quiet African spaces amongst the forest animals and seamlessly pivoted to using her influence as one of the most recognizable faces on Earth to stand in front of world leaders, corporations, philanthropists and conservationists.

She called on everyone to do more to help all creatures. She firmly demanded that humans stop exploiting animals and abusing them for entertainment and sport, and that we stop destroying the planet with pollution and the wanton destruction of habitat. She spoke out against factory farming, the cruel taming of wild elephants, the breeding of dogs in puppy mills, the bear bile industry and trophy hunting, and the trafficking of wild animals in the global trade.

And by working with youth, she changed the present and the future of animal advocacy. In 1991 she started the Roots and Shoots program, which pulled together young people and gave them the power to start their own initiatives to help animals and the planet. The program now operates in over 100 countries around the world, continuing her gift of inspiring youth to take action for animals and the environment.

It was her ability to spread her passion to children that is also one of my favorite personal memories of Jane. She was kind enough to invite my 10-year-old daughter and an exchange student from Costa Rica who was staying with my family to come spend the afternoon with her when she was in Washington, D.C., as part of one of her many trips around the globe promoting animal welfare, conservation and environmental values. She spent hours talking to them about the importance of girls focusing on science, and the need to take personal action to help animals. And while I had been fruitlessly trying to channel my daughter’s love for animals into advocacy for years, it only took a few hours with Jane to get my daughter to start the first Roots and Shoots chapter at her elementary school.

You would think Jane, with all these accolades, would be an intimidating figure. But she was also just immensely fun. One of my fondest memories is watching her being serenaded by musician Dave Matthews at her 80th birthday party celebrating her career, drinking whiskey at midnight and spending time talking until the early morning with each of her guests.

Other personal memories with Jane that I will cherish: She publicly but lovingly scolded me for not speaking out louder on behalf of a particular animal issue she was working on. She called me in the middle of a family vacation about a group of elephants in need of rescue and insisted that I settle an argument about how to best help them.

These are all fantastic memories I have of Jane. But I need to acknowledge that I was not unique—Jane shared her passion with conservationists and animal welfare professionals everywhere. In her work with us, she was not only fearless, she was also tireless. On the global stage, she would use her celebrity to help any cause for animals, lift other advocates and right wrongs against animals and nature wherever she could. Her passing is a tremendous loss to the planet, but her legacy is rich and wonderful beyond words, and she leaves behind a world made better by her.

Jeffrey Flocken is chief international officer at Humane World for Animals.