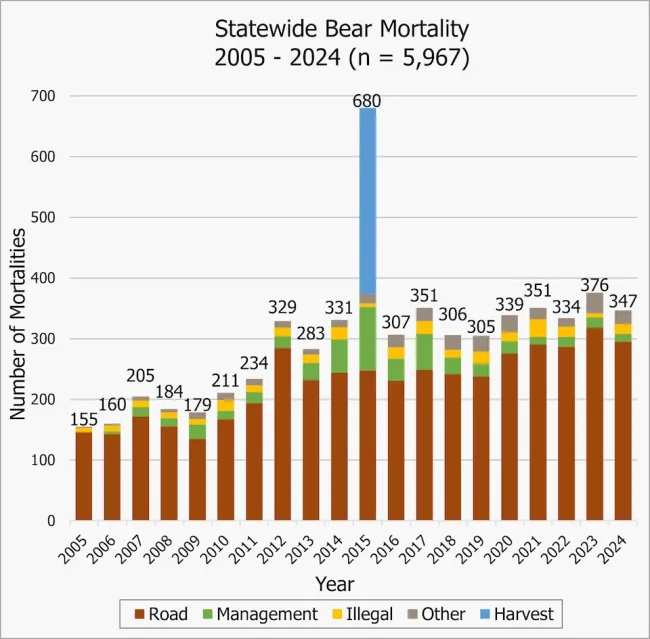

Editor's update: During the 2025 hunting season, a total of 52 bears were killed. Almost half of them were female.

In 2015, Florida wildlife officials allowed the state’s first black bear hunt in more than 20 years. The hunting season was supposed to last a week. But two days after it started, hunters had already killed 304 bears, rapidly approaching the statewide quota of 320. Florida officials abruptly stopped the hunt. In two of the four hunting areas, hunters killed more bears than was allowed. The eastern part of the Florida Panhandle had a quota of 40 bears, but hunters killed 114.

The types of black bears killed also raised concerns. Almost 60% of the bears were female. Of those bears, 21% were lactating, meaning they most likely had cubs depending on them for survival. Regulations stated that hunters couldn’t kill bears less than 100 pounds, but 13 bears were below this weight.

“It was mayhem,” says Kate MacFall, Humane World for Animals Florida state director. After the shortened hunting season ended, Florida did not authorize any bear hunts for a decade.

That changed this August when the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission announced it would reopen black bear hunting in the state, starting with a three-week season this December. During the 2025 season, hunters will be given permits to kill a total of 172 bears.

The reopened hunt comes a year after Florida passed a law that allows people to kill black bears for perceived threats to their safety, their pets’ safety or “substantial damage to a dwelling.”

Anton Sorokin/Alamy Stock Photo

What to do about black bears?

Bear troubles in your neighborhood? Bird feeders and unsecured pet food, garbage and grills may be bringing them to your back door.

Black bear hunting by the numbers

Florida is not an outlier. Of the at least 40 states with black bears, 35 allow them to be hunted.

The number of black bears killed by hunters is “just jaw-dropping,” says Wendy Keefover, a senior principal of carnivore protection at Humane World. Our newly released report reveals that more than 1 million black bears were legally hunted in the U.S. between 2000 and 2024. An unknown number of cubs died during this timeframe after their mothers were killed by hunters.

And black bear hunting is growing: In 2000, around 34,000 bears were hunted and killed compared to almost 50,000 in 2024.

N/A

Also shocking are the methods hunters use to kill bears, Keefover adds. Twenty states allow hunters to use dogs to track and chase black bears; 13 states allow “baiting,” where hunters lure bears to an area with piles of food; and seven states allow hunters to kill bears during springtime when some females have newly born cubs, the animals are lethargic and vulnerable after spending winter in their dens.

In Alaska, home to an estimated 100,000 black bears, protections have fluctuated with changing federal administrations. In 2015, the National Park Service banned certain extreme hunting methods, including bear baiting and using artificial light to kill hibernating mother black bears and cubs in their dens in Alaska’s national preserves. That rule was reversed in 2020, a decision we sued the federal government over. While the Biden Administration reinstated the ban on bear baiting, in January of this year, President Donald Trump signed an executive order effectively directing NPS to once again allow baiting of brown and black bears in Alaska’s national preserves.

Why black bears are coming to town

These hostilities are not new. Humans have shaped the lives of black bears for centuries, often through indiscriminate killing.

After European colonists arrived in America, they hunted black bears in massive numbers and converted vast swaths of forests into farmland. By the start of the 1900s, black bear populations reached a likely low point. Strong legal protections have helped the bruins slowly recover.

But bears today are struggling to fit into a world much different than it was centuries ago. Black bears have lost much of their natural habitat to human development. They often have to cross highways, suburbs and parks while foraging, finding mates and raising their young. Vehicle collisions are a growing threat.

iStock.com

Pushed closer to people and driven by their incredibly strong sense of smell, bears are learning that human spaces are full of easily accessible food sources.

While bears generally prefer to forage on natural foods such as berries and nuts, these foods are becoming less abundant due to climate change-induced weather events and other factors. Human-bear conflicts tend to increase in bad foraging years. And as our winters get hotter, some bears are hibernating less or forgoing it completely. Awake in winter when natural food is scarce, bears are entering towns and getting into more conflicts with people.

Most conflicts between humans and black bears involve indirect issues such as bears getting into bird feeders, backyard chicken flocks or garbage cans, data from state wildlife agencies show. It’s incredibly rare for a black bear to seriously injure or kill a human. Still, conflicts can become a problem. State wildlife officials often turn to hunting as a solution.

“We hear it a lot [from] states that we have to hunt bears in order to reduce conflicts,” says Keefover. But sound science just does not support that belief, she adds. In states where hunters are allowed to bait bears with food, hunting can actually increase the rate of conflicts.

Because hunting does not address the root causes of human-bear conflicts, incidents will continue to occur as long as bears are attracted to human settlements, Keefover and other wildlife management experts say.

Bears at risk in the Sunshine State

Another common argument Keefover hears is that hunting helps prevent bears from becoming overpopulated.

Florida’s black bear population hit a low of a few hundred individuals in the 1970s. The population has been slowly growing since then. State officials estimate that 4,050 black bears now live in the state, but Keefover warns this number is based on decade-old data. “Basically, Florida doesn't have a good idea of what their bear population is statewide.”

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

These bears are scattered across small subpopulations hemmed in by habitat loss and urban sprawl. They can’t easily intermingle—vehicle collisions cause the vast majority of bear deaths in the state—and Keefover worries these isolated groups don’t have enough genetic diversity.

Adding black bear hunting on top of these existing threats could jeopardize Florida’s bear population, MacFall says. In fact, she adds, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission already had to reduce the 2025 hunting quota by 15 bears following a population study of one of the state’s black bear subpopulations.

The situation probably isn’t going to get easier for Florida bears. Not only is Florida the third most populous state, it also has the fastest-growing population according to the 2022 U.S. Census. At over 23 million residents today, Florida is expected to expand to almost 34 million by 2070.

Construction and human development are rampant in the state, says MacFall. “It's out of control. Bear habitat is being deteriorated as we speak. And then [people] wonder, ‘Oh, these bears are in the neighborhoods?’ Well, yeah, of course they are.”

The inherent cruelty in black bear hunting

In addition to concerns about how hunting will harm the future of Florida’s black bear population, MacFall is also horrified by the methods hunters are allowed to use. Under the rules approved in 2025, hunters can lure bears onto private land with piles of natural foods, use bows and arrows to kill bears, and, starting in 2027, use up to six dogs to track and chase bears.

“Floridians are already upset that black bears will be hunted but allowing bears to be chased by packs of dogs is particularly cruel,” says MacFall. “And according to our poll, 89% of Floridians oppose hounding.”

Hunters using “hounding” dogs send a pack of GPS-collared canines into the woods to find and chase black bears. Bears can be forced to run from dogs for hours on end before they finally climb up a tree for safety. Hunters then come in for an easy shot.

N/A

It’s not just the targeted bears who suffer. Dogs can kill other animals such as bear cubs or be killed themselves, especially when baiting is also allowed. Bait stations encourage wild animals to congregate into an area, Keefover explains. Wild animals may fight each other over the food or attack hunting dogs who come into the area.

Hunting bears with archery equipment can also expose them to needless suffering. “It's really hard to kill a bear with a bow and arrow because they've got really thick hides, thick bones, and you have to get a clean shot,” Keefover says. “One must target a vital organ to kill the bear. And so, if hunters don't do that, the bear can just run off and then die of blood loss.”

Bill Lea/Bill Lea Photography

A peaceful future with bears

Florida’s 2025 bear hunting season starts next month. MacFall says it’s heartbreaking to think about. But she’s encouraged by all the Floridians who have advocated for the bears and the communities that are implementing strategies to peacefully coexist with their wild neighbors.

One such community, Seminole County passed an ordinance in December 2015 requiring residents to secure trash from bears. That year, residents made nearly 700 complaints about bears. By 2024, that number dwindled to 308.

Measures such as these are “so doable,” says MacFall. They also represent the values of the many people who live alongside bears and want to keep them protected. After the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission announced its plan to reopen black bear hunting, it received more than 13,000 comments. Around 75% of them opposed the plan.

“Floridians really, really love their black bears,” says MacFall. “We'll always continue fighting for bears.”

Related Stories

Margocat/Alamy Stock Photo

In Durango and other parts of the West, the bears are coming to town—and people are learning what to do so everyone, human and bear, stays safe.

Wendy Keefover/The HSUS

Proposed legislation now threatens the Endangered Species Act, gray wolves, grizzly bears and hundreds of other animals.

Britta Jaschinski

Photojournalist Britta Jaschinski documents illegal wildlife products confiscated at the U.S. border.