Shortly after dawn, two men carrying what look like automatic weapons head toward blinds in the yard of Enid Feinberg, northeast of Baltimore. The SUVs parked in Feinberg’s driveway are plastered with bumper stickers expressing outrage at the people who stalk deer in her subdivision, and a sign on the three-car garage warns hunters away. Feinberg has a running feud with a neighbor who bags deer, and she keeps careful watch, through closed-circuit television, on the 14 acres she and partner Lierra Lenhard own: The woods that spill over their property connect to land where the city allows bow hunters to cull; every fall, the two women find deer with arrows in their bodies and festering wounds. Once, Feinberg chased off a camouflage-clad bow hunter she spotted crawling along the fence that borders their backyard. “We’re defending our home,” she says.

Yet here, at Feinberg and Lenhard’s invitation, are Anthony DeNicola, sharpshooter for hire, and his assistant, Charles Evans, dressed in Carhartt and ready to take aim at the deer the women leave corn out for each morning: DeNicola, whose company, White Buffalo Inc., has culled more than 10,000 deer, collecting fees from communities like Greenwich, Conn., and Princeton, N.J. The two men tuck themselves away—DeNicola in a shed and Evans in a truck. Feinberg has put out apples to mask their scent. Volunteers inside the house feed them reports off six TV screens linked to professional grade cameras that can bring objects into focus from up to half a mile away.

Evans and DeNicola are not looking, as hunters often do, for bucks, and they are not using bullets or aiming for the head or heart. Hired for the weekend by the Maryland nonprofit Wildlife Rescue Inc. (of which Feinberg is president), they are searching for does without tags on their ears—ones who have not yet been sterilized. They will hit them in the rumps with radio-transmitter-equipped tranquilizer darts so the deer can be captured for surgery. It’s part of an experiment to reduce deer numbers humanely. Within an hour, Evans gets a doe who bolts off Feinberg’s property and runs through trees and fields before collapsing. Soon after, DeNicola gets two sisters who head down a power company right-of-way before falling in snow-frosted leaves that carpet the woods.

James Berglie/For the HSUS

James Berglie/For the HSUS

Wildlife Rescue volunteers go out in an all-terrain vehicle to pick up the deer on stretchers and transport them to Feinberg and Lenhard’s garage. There the three does—pregnant, as almost all healthy does are in February—have their ovaries removed in a procedure perfected by Wisconsin vet Steve Timm over the past six years with DeNicola, a Yale- and Purdue-educated wildlife biologist. Timm performs the surgeries beside Dr. Tamie Haskin of Wildlife Rescue, one of a half dozen vet volunteers he’s trained around the country (with their donated time, the cost of each operation drops from about $1,200 to less than $500). In 30 minutes—the animals’ blood circulation and breathing suffer when they’re on their backs for longer—Timm and Haskin slice into each abdomen, locate the fist-sized uterus, cut out the fingernail-sized ovaries on either side, cauterize the wounds, stitch up three layers of muscle and close with a row of surgical staples.

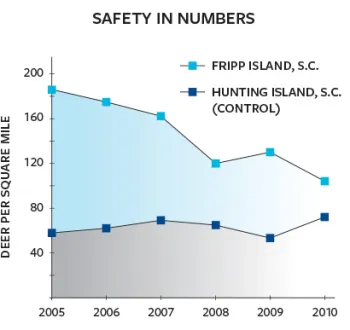

It’s a procedure Feinberg hopes will put an end to suburban communities killing deer who eat gardens or dart in front of cars. Even if communities don’t choose to sterilize deer, she hopes news of the technique’s success at least gets them thinking about other nonlethal means, like the contraceptive vaccine PZP (which the HSUS has funded and championed). Ten does will be sterilized that weekend in Feinberg’s garage—including one with entry and exit wounds from a hunter’s arrow—bringing to 69 the total “spayed” over the last four years. The method is effective: These days, eight out of every 10 deer sighted by Wildlife Rescue volunteers around Feinberg’s house have already been sterilized. They will never get pregnant again. And, unlike deer who are killed, sterilized animals will continue to occupy their half-mile ranges, discouraging other deer from moving in. Given those kind of results, the HSUS—which uses innovation and technology to develop humane solutions to wildlife conflicts—has embraced sterilization as an option for reducing deer numbers. This winter, the organization gave $3,000 toward a sterilization project in Fairfax City, Va., and started planning to train staff to assist with surgeries (Stephanie Boyles Griffin, HSUS senior director of wildlife response, attended the sterilization at Feinberg’s as an observer).

The important thing, says Boyles Griffin, is for agencies and communities to have humane options; which one they choose will depend on the circumstances. In Washington, D.C.’s Rock Creek Park, where sharpshooters from the federal Wildlife Services agency have finished a second winter of killing deer, she hopes that the National Park Service will adopt surgical sterilization. “It will save a lot of lives.”

Richard Ellis/For the HSUS

Just over a century ago in this country, white-tailed deer were near extinct due to habitat loss and commercial hunting—so rare that in 1933 Stephen Vincent Benet described them as ghosts: “When Daniel Boone goes by at night / The phantom deer arise / and all lost, wild America / Is burning in their eyes.” But even as he wrote, the forest was coming back across abandoned farms in the northeast, and hunting restrictions were helping restore deer. Later, as Americans built the country’s suburbs and exurbs, they created the perfect environment for deer, full of meadows and forest edges that function, however unintentionally, like a giant park designed just for them. Multiplying to fill this ideal habitat, the species grew from fewer than 15 million in 1980 to as many as 30 million today—nearly the number when Europeans first arrived in North America.

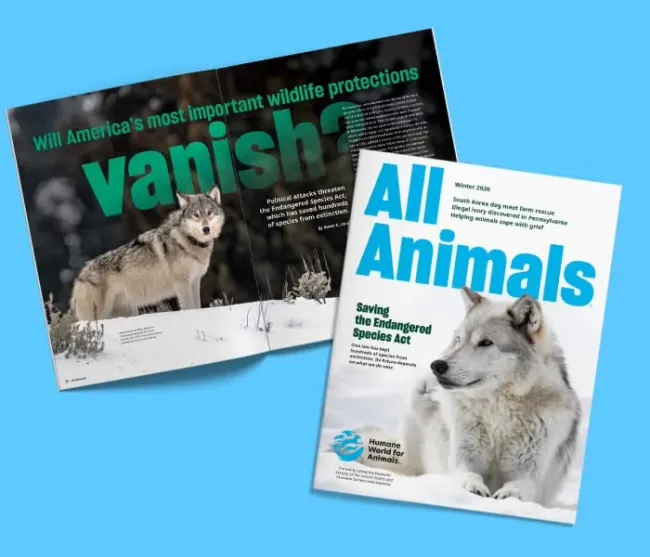

In communities across the U.S., deer denude carefully planted yards, wander into busy roadways (causing more than a million vehicle accidents each year), and raise the specter of Lyme disease (though white-footed mice are the primary host, and there’s no correlation between deer densities and human risk of Lyme). Angry calls to eliminate deer have led to a patchwork of controversial, often ineffective kills, including sharpshooting that must be repeated year after year (DeNicola compares it to cutting grass) and culls that invite amateurs with bows and arrows into residential neighborhoods and hunters with rifles into public parks. But public safety concerns, outcries from residents and legal action are blocking many culls, including a plan to hire Wildlife Services to kill thousands of deer in eastern Long Island. And recent breakthroughs in fertility control mean killing is no longer the only option. After decades of research, scientists and animal advocates are readying nonlethal methods for widespread adoption: Surgical sterilization of does is one. Vaccinations with the contraceptive PZP, developed over two decades with the help of the HSUS, is another.

Since 1995, the HSUS’s Rick Naugle has labored in a little corner of suburbia to test the PZP vaccine and perfect its delivery. The campus of the federal National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Md., lies 20 miles northeast of Washington, D.C. It’s a deer paradise: wide lawns, ponds, stands of mature trees, and plantings of saplings, each wearing a plastic sleeve to protect it from hungry does and from bucks rubbing velvet off their antlers. The grounds are fenced but deer jump the 6-foot-high barriers or just walk around them, entering at the gates. Motorists driving by on Interstate 270 see deer grazing like cows. About 200 live here and Naugle knows each of them. More importantly, they know him, which has made his job difficult.

While PZP is in the experimental stage, record-keeping requirements mean every one of the NIST deer has had to be darted with a tranquilizer and tagged before being vaccinated. In the early years, deer had to be darted again soon after because the first dose of PZP had to be immediately followed by a booster. Today, a new formulation with timed-release pellets means does don’t have to be darted again for two to three years. But then the challenge comes: Each time deer are darted, they grow warier. After 20 years, the deer at NIST are pretty damn smart, says Naugle; they long ago stopped coming to bait or entering a box trap. “When I first started I could dart 10 to 15 a day. Now I’m lucky if I get two.”

In February it’s finally warm and dry enough to resume darting deer (tranquilized deer might suffer hypothermia in cold or rain). On this day, Naugle is trying to dart deer who have lost ear tags or never had them. First he takes some practice shots. (Hitting the mark is tricky. The gun fires at a low velocity and the dart is big and heavy. Unlike a bullet, it travels slowly, rising and then falling in an arc, so a darter has to get within 20 to 30 yards even without wind.) Then Naugle begins a slow and patient tour of the campus in an all-terrain vehicle, the darting gun, a converted .22, balanced neatly between the corner of the windshield and his thumb.

He quickly spots a doe he’s looking for. But the deer, who’s been darted before, spots him too. And so when he is getting just about close enough to dart her, she descends a steep slope with other deer, crosses a stream, and starts grazing on a hill on the other side, out of range. Naugle can’t follow, so he circles around until he’s approaching her from the other side. He’s just drawing near when, as before, she evades him, bounding off with the herd back across the stream. Naugle sighs. That day he never does get her. Instead, an hour later, rounding a clump of trees on another part of the campus, he sights a doe who has never been tagged, shoots, and watches as the deer walks off a little ways, staggers, and then goes down in the winter-pale grass. After waiting 20 minutes to make sure she’s out, he approaches. A buck stands nearby. “You nut,” Naugle says to the deer. “What you doing? Protecting her?” He slips a mask over the doe’s eyes so she doesn’t startle, pulls her tongue out of her mouth, takes her temperature, checks her heart rate, and puts a tag in her ear. Bold black numerals spell out the number of deer Naugle has darted at NIST: 991.

Naugle grew up in southern Pennsylvania and would hunt in the mountains, pursuing deer when they were much harder to find. While he was earning a degree in wildlife management from Penn State, one of his professors introduced him to Jay Kirkpatrick, director of the Science and Conservation Center in Montana, who produces PZP, or porcine zona pellucida (it’s currently derived from pigs, but the HSUS is pursuing development of a nonanimal alternative). The vaccine causes female mammals to produce antibodies that prevent conception. For this reason, it’s called immunocontraception. In 1988, Kirkpatrick began testing PZP on the wild horses of Assateague Island. Naugle volunteered. He followed mares around, waiting for them to pee in the sand so the urine could be tested to show whether they were pregnant. That research provided the first evidence from any species that PZP worked in the field.

If it works, we will have done a great thing, not only for us but for a thousand other communities.

Peter Swiderski, Hastings-on-Hudson mayor

Working with Rutberg and skeptical officials at the DEC, Swiderski came up with ways to measure whether PZP succeeds. The village will install camera traps to estimate the size of the deer population over time and build enclosures in the woods to measure how plants grow where deer graze and where they cannot. The police will, as always, record deer-vehicle accidents. And 40 residents will place hostas—favorite deer food—in their yards as sentinels, tracking whether and when they get eaten. No one, including the mayor (or even Naugle, Boyles, or Rutberg), is confident that PZP is the answer in Hastings-on-Hudson. But Swiderski has assembled a group of 120 volunteers who are willing to try.

“If it works,” Swiderski says again and again, “we will have done a great thing, not only for us but for a thousand other communities. If it doesn’t work, we won’t have killed any creature, we won’t have split the community, and we’ll also know it doesn’t work in this kind of community.”

Richard Ryan lives in Uniontown, a neighborhood with blue collar roots and small houses where few worry about deer. Ryan has never seen one in his tiny yard, but he likes to walk his beagle in the park at the foot of his street, where the deer browse, and he worries the deer may be damaging native plants, harming the bees and birds and other animals who depend on them. Since he crunches data for a living, he’s agreed to compile reports of sightings from across the village. If the number of reports declines over time, presumably that will mean that the number of deer, or at least concern about the number of deer, has declined.

Daniel Lemons, a biology professor at the City University of New York, lives with his wife in the heights overlooking Reynolds Field, where deer come out of Hillside Woods to graze on the high school football field. Soon after he moved to the village from New York City years ago, Lemons could appreciate the beauty of deer when he saw them. Since then he and his wife have had Lyme disease, which they connect to the deer (though there’s no proof of that), and his wife has stopped going outside to garden. The couple has lost more than $1,000 worth of plantings to deer and spent money on a backyard fence and gates. In front of their house, the deer have gobbled up the ivy and started nibbling at the pachysandra. Lemons will coordinate volunteers helping Naugle track and dart.

Irene Jong, a doctor, lives with her husband and three sons in the highest part of the village, just above Hillside Woods. This year, her family put up a backyard fence. They were tired of the trail of droppings the deer left as they traveled through, trampling the grass. Jong will distribute hostas to neighborhoods all over Hastings-on-Hudson; she expects the one she’ll place in her own front yard will be quickly eaten. That’s why, although she wants a garden, she hasn’t yet planted one. It would just be an offer of food, she says. “I don’t see starving deer. They look like the pigeons in New York.”